Two Paths of Forests After Fire

Written and illustrated by Gino Savaria

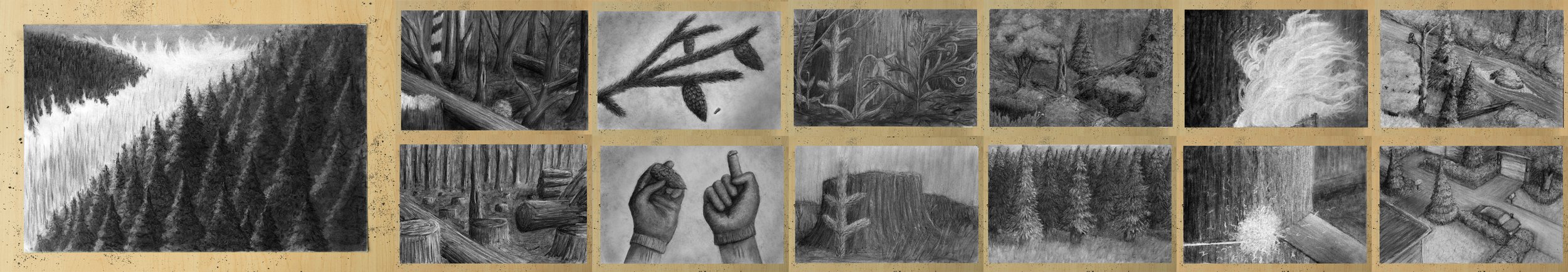

Nature or nurture? Gino Savaria guides us through two approaches to post-wildfire reforestation in Western Oregon. Using charcoal he collected from burned trees in Sisters, Oregon, he explains how different methods of land management produce different forests. Gino presents these differences based on conversations with foresters, land managers, and ecologists. Follow along as he takes you on a journey through the lives of two types of forests after fire, the wild and the farmed.

The Fire

Each year, before fall winds cool the air, a fifth season—smoke season—inserts itself at summer’s end. Heatwaves, droughts, and dry vegetation in concert with years of fire suppression allow this new season to take its place on calendars across the United States.

In Western Oregon, wildfires singe some forests and leave others ashen and bare. These fire-damaged landscapes immediately begin to regrow, but recovery depends on the severity of the fire and the type of forest.

As these forests regrow, the strategies that landowners and managers use shape what they become. Like farmers, whose top goal is crop yield, one forest manager may plant thousands of acres to grow conifers for timber production. Another forester may allow the land to regrow without human help, leaving nature to nurture a new forest. We’ll follow these two pathways to new forests, but variations exist in between, ranging from lightly managed to heavily managed.

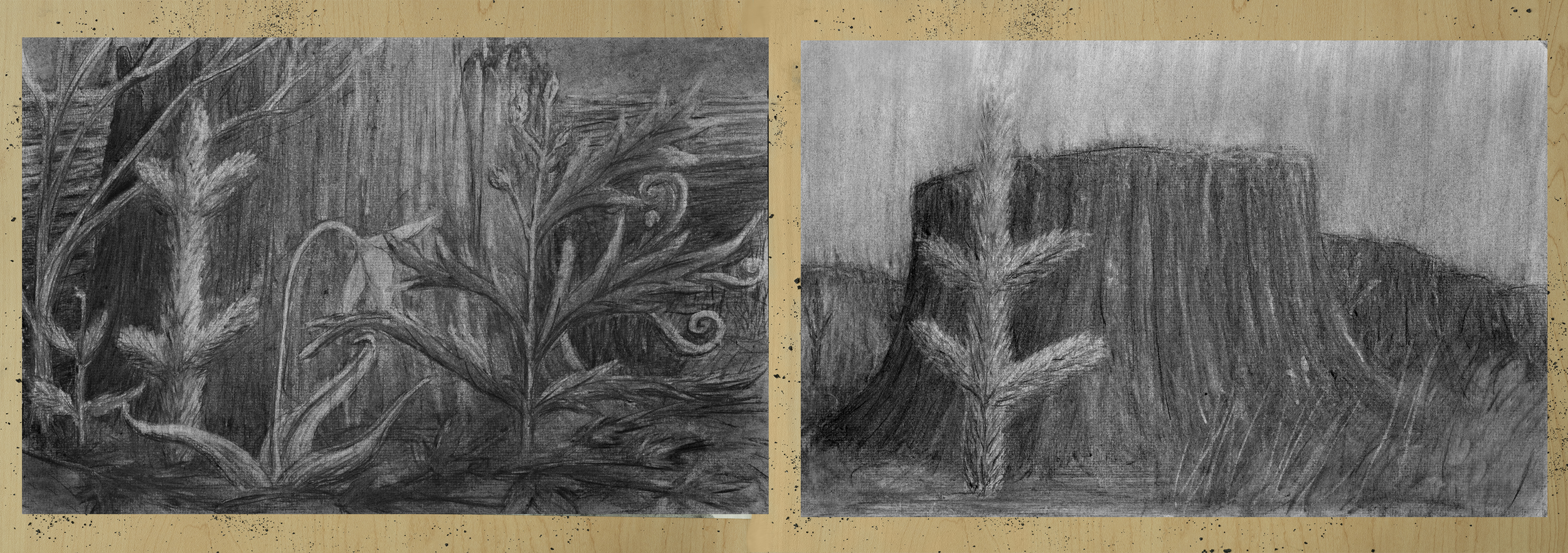

The Burn

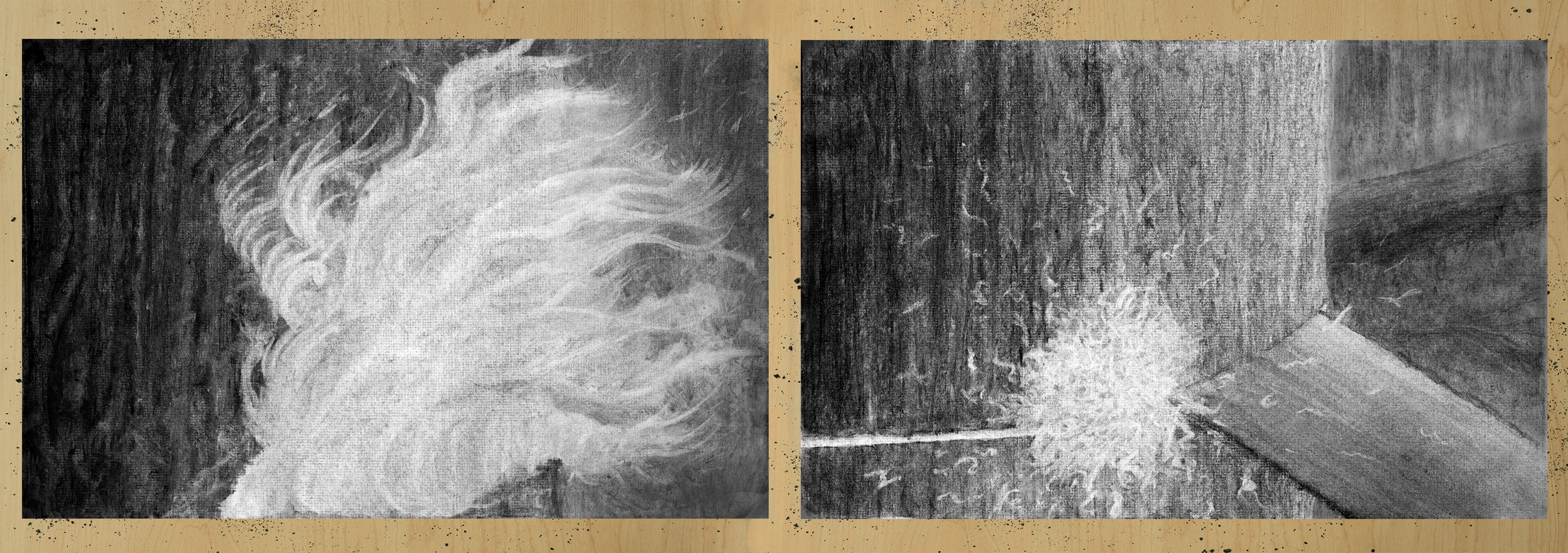

A burned forest left on its own at first seems desolate. Intense fires can break apart root systems, causing trees to fall. Conifers with unburned crowns and cones can seed a new generation of trees. Those that burn will stand as hollow skeletons until they too fall. While this charcoal-coated landscape creates the impression that little life remains, new shoots and leaves bring color back to this scorched land.

As fire tears through a farmed forest, it can destroy the commercial value of a landowner’s trees. If stands are mature, salvage crews swarm in, cut down, and haul away any saleable wood. Trees that cost more to remove than their value at market are left to decompose and provide soil nutrients.

The Seed

Once timber has been cut and removed, the land needs new trees. Forest managers replant with seeds bred for high yield and growth rate from trees whose ancestors grew nearby. Tree nurseries contract to grow these seeds into seedlings, this can take up to two years.

Sometimes wildfires burn more acres than normal, causing a seedling shortage. After several large fires of 2020 and 2021 in Western Oregon, nurseries were unable to provide enough seedlings for landowners to replant their land.

Evergreens like firs and pines rely on seeds to reproduce. Flowering trees must exchange pollen for cones to develop. Once they mature, cones open to send winged seeds sailing along air currents through the forest.

Each seed holds enough energy for a new seedling to sprout, but unsprouted seeds can become food for small animals like squirrels and birds. By storing food to eat later, these forest animals also help spread seeds that could eventually sprout.

The Seedling

Land managers encourage dense tree stands by planting up to twice as many seedlings as they hope will survive. Once seedlings are growing, workers thin competing plants by hand or by spraying herbicide around seedlings. Once new tree stands are established, work slows down. Managers check tree growth every few years to determine whether competing plants are removed or seedlings are replaced.

Conifer seeds that sprout in wild forests must overcome competition from other plants. Herbs, grasses, and other tree species often have a head start in the quest for soil nutrients, water, and sunlight. This can threaten the survival of young conifers, slowing their spread across the forest.

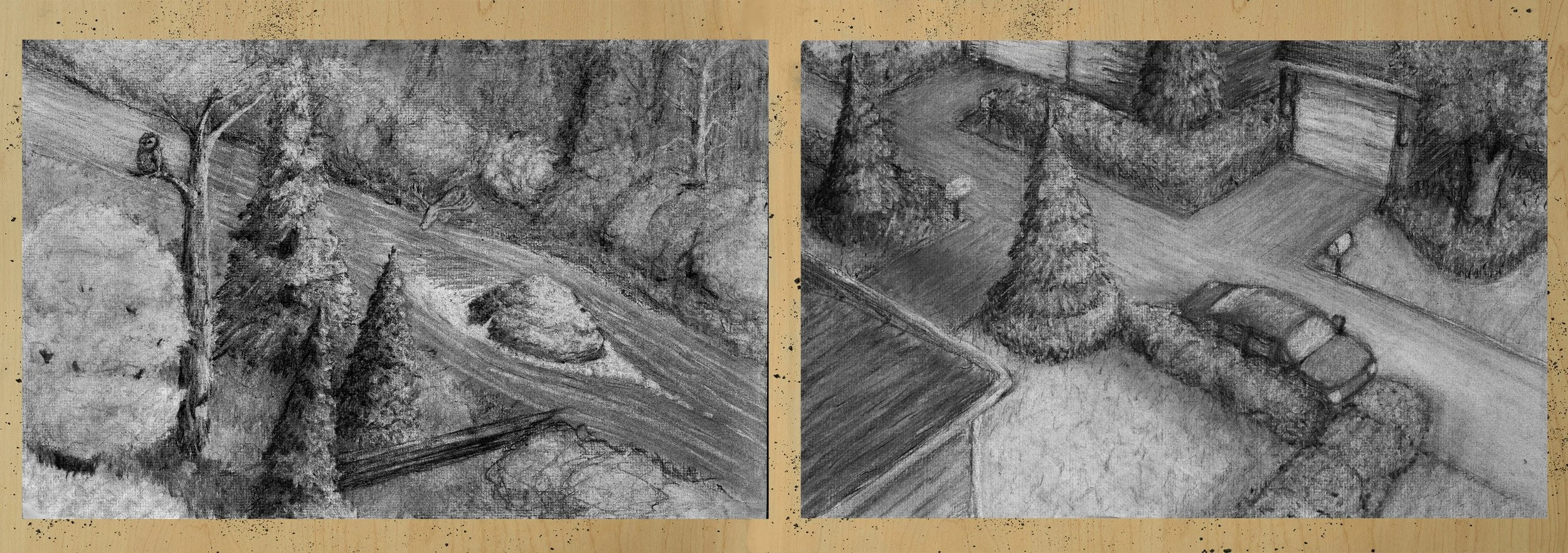

The Forest

As years pass, wild forests form patches of trees separated by meadows of shrubs and grasses. Within these stands, generations of hardwoods and conifers coexist, but signs of the burned forest recede. Across the landscape, dead trees remain. Some decompose on the forest floor, blanketed by moss and foliage. Other standing dead trees loom over their slow-growing kin.

With a head start and fewer plants to compete with, conifers in a tree farm can grow rapidly, maturing quicker than their wild cousins. Crews thin dense forests to help growth rates. This allows remaining trees to capture more sunlight, water, and nutrients.

The Death

Time determines the fate of trees in a wild forest. Changing temperatures and precipitation from climate change threatens their survival. Some trees may live for centuries, while others are unable to withstand the threat of drought, fire, and disease. Eventually, many less managed forests can also be harvested for timber.

People who plant trees may not live long enough to see them harvested. Some forests are cut on a 40-year cycle, but other stands may take fewer or more years to reach harvest age. Once trees are old enough, crews cut and send them to sawmills. A cleared forest signals that the time for planting seedlings draws near.

The Value

Whether wild or farmed, Pacific Northwest forests offer value to the people around them. How these forests are grown and managed determines this value. A natural forest can support rich biological activity like diverse plant and animal populations. While natural and farmed forests can both control soil erosion and provide clean water, farmed forests also support local economies with jobs, paper, and lumber. As wildfires clear more land, we decide the fates of our future forests: nature, nurture, or somewhere in between.